Deja Vu, 100 years Later

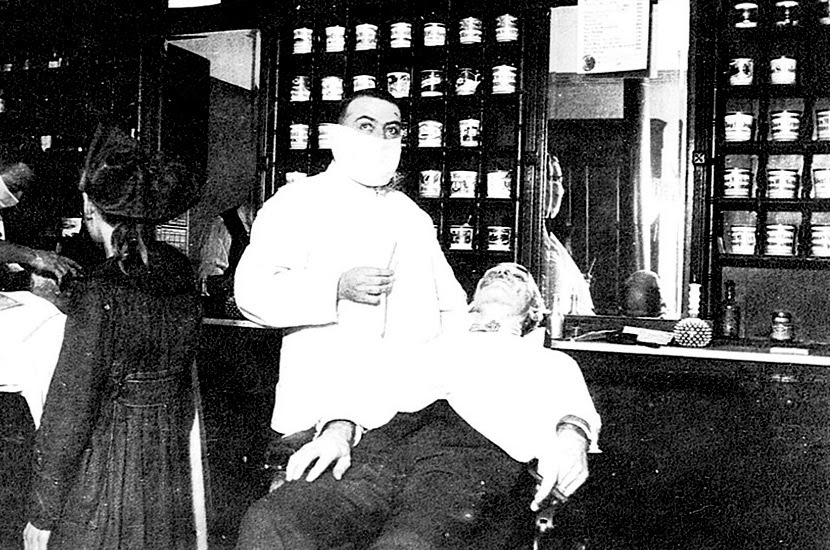

A deadly pandemic. Masks. Social distancing. Sound familiar?

As 2020 agonizingly trudges on, the phrases “normal” and “unprecedented” seem to have taken on new life. With every new disheartening statistic and miserable milestone, we’re constantly reminded of the novelty of the times. But a look back at Chicago during 1918-1919 and the Spanish flu reveals stunning similarities that lead one to question really how new these events are, and whether looking to the past may lead to a better response to our nation’s greatest current threat.

Both COVID-19 and the Spanish flu made their way to the U.S. in March of their respective years, but unlike COVID-19, symptoms of the Spanish flu included the normal effects of the common flu compounded with the victim turning shockingly blue due to lack of oxygen, as their lungs filled with a viscous blood-like substance.

Eerily prescient national arguments between what we now know as “anti-maskers” and the majority of the population who supported these sensible precautions prevailed at the time. Those refusing to wear masks were often lampooned as “slackers,” and groups like the San Francisco Anti-Mask League held events protesting restrictions. Anti-maskers were uncommon, however, according to epidemiologist Howard Markel, a somewhat baffling notion considering the sheer amount of anti-mask outbursts and sentiment present in news and social media now.

After about two years, Chicago emerged better off in terms of death than other big cities, but not at all unscathed. 8,500 Chicagoans died after two years, according to historian and television producer Geoffrey Baer, an ominous number considering the current deaths from Covid-19 are around 5000 before even the first year. Chicago has not been left untouched by the coronavirus, either. With 5,469 deaths in Cook County as of Oct. 30, our area has felt the virus’s chilling effects, which have shuttered many of the city’s businesses and temporarily closed schools.

Most of these deaths came in what we now know as a “second wave,” which the United States is experiencing as of this writing, and what has led forecasters to predict a dark winter.

Baer credits Chicago health commissioner John Dill Robertson for the relatively low death rate. Robertson was a Fauci-like figure at the time who banned public gatherings, says Baer. These then-harsh rules were likely the reason why Chicago emerged better off than cities like New York, according to the U.S. National Library of Medicine; New York ended with around 31,000 deaths by the dawn of 1920. A clipping from an Oct. 4, 1918 edition of the Chicago Tribune and a statement from the newspaper demonstrates that the public was perhaps not mentally prepared for the oncoming sickness, regarding the warnings of doctors as doing little more than causing unnecessary panic, even mentioning Robertson himself.

“Health commissioner Robertson has done something to allay a feeling which had been created by zealous medical authorities,” the Tribune wrote. “There was too much highlighting of predictions that the city was certain to be swept by a deadly plague.”

Hindsight is 20/20, but as the current pandemic and recently released interviews with President Trump have shown, there’s a fine line between panic and a healthy fear of an unknown enemy. A platform of “not spreading panic” is simply dangerous indifference, and does little to protect those at risk, instead letting them know how insignificant they are in the eyes of the state.

The pandemic of 1918 did end, but not with a vaccine. Those with it, in blunt terms, either died a gruesome death or their body suffered through the terrible pain and somehow formed an immunity,. Either way, as the cases rise and deaths continue, it’s hard to find what, if anything at all, has changed.

Your donations directly fund the Lane Tech student journalism program—covering essential costs like website hosting and technology not supported by our school or district. Your generosity empowers our student reporters to investigate, write, and publish impactful stories that matter to our school community.

This website is more than a publishing platform—it's an archive, a research tool, and a source of truth. Every dollar helps us preserve and grow this resource so future students can learn from and build on the work being done today.

Thank you for supporting the next generation of journalists at Lane Tech College Prep!

Aidan is a senior in his second year at the Champion. In his spare time, Aidan likes reading, watching and playing soccer and re-watching The Sopranos....