Humanities answer the unanswerable

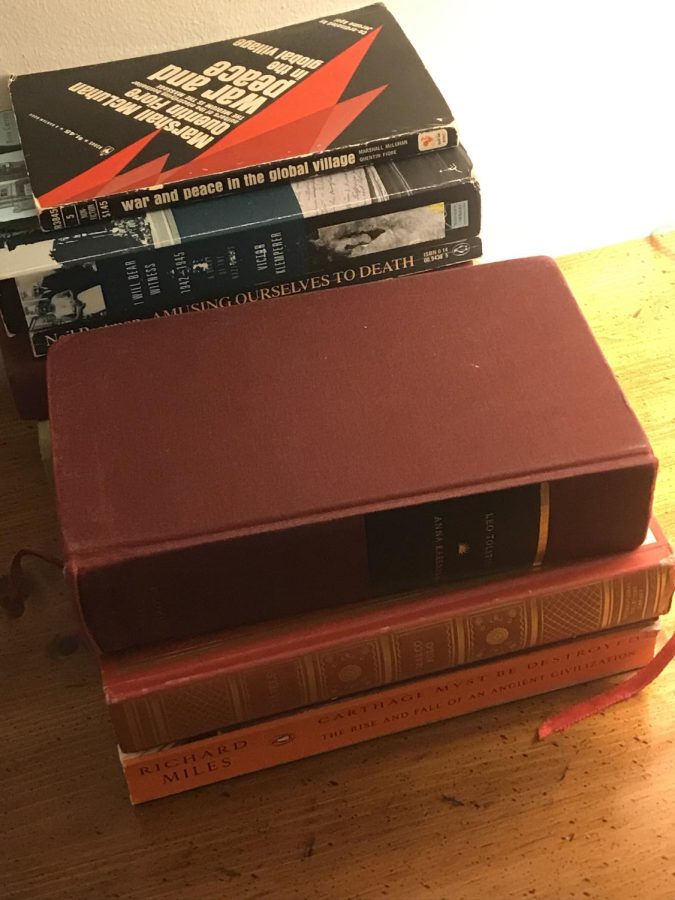

The stack of books I may or may not ever finish reading.

Where does work end and life begin? For many it’s the end of a shift, with the experience of walking out of a place and expelling it from your mind. Meaning work is work and life is life — the difference profound and immediate. It seems peaceful and very much is, but I question the concept of finishing and forgetting. In the end, I want to know more. I want to know why.

Why?

It’s on my wall; a twelve by eight piece of paper with the letters W, H, Y scrawled across in sharpie sits there to remind me to think (obviously) “Why?” I am reminded that, instead of reacting, I should find out the internal, or external, reasons for my actions and those of others. It seems simple, but it’s not. Those answers come hard, really hard, and need a little help to be found.

So where to find them? Like most others throughout history, I could look to religion. I could find solace in the answers provided by the prophets and their texts. For me, however, there is too little empiricism — I’ve never been able to put my trust in faith. Then, well, science seems like the next most logical outlet. Empirical answers to difficult questions are very attractive. Yet, I don’t feel that people can be summed up by the parts which make up their body. There must be something that makes us different from our animal counterparts; I feel it’s our language, our writing and therefore our history.

Without language and writing, who could remember what happened in the past? History would be confined only to living memory. Meaning, well, how could you make any meaning of it?

“English kind of gives us the ability to just look at life in the world around us and just make meaning from it,” English I and III teacher Joshua Smith said.

Honestly, you don’t need to be a scholar or an academic to make meaning out of the world. In fact, you already have. It might be just like your parent’s, or Joe Rogan’s, or truly your own but you’ve made some. What matters is that it’s there. We all have some guiding theory and principle which shepherd’s us through life. The key to unlocking them, though, are stories. Above or beneath the surface, past or present, stories let you into the world of others.

It’s why I joined the Omega program at Lane. I felt I could best answer “Why?” around those who had a desire to find that answer. What I have discovered, though, is that, while informed by classes, answers come best through one’s own observation.

“I believe that literature is art and art depicts life. Right? So if you’re reading Shakespeare, let’s say Macbeth, and you look at power, and you look at gender roles, and you look at ambition and greed and all these different things,” Smith said “You see this every day in your daily life in general. So it’s just kind of cool to make sense of the world.”

Books, even nonfiction ones, are written down stories. That seems obvious, but it’s not. Writing and therefore books allow us to keep a memory of what has happened, and impart what wisdom we have onto the next generations. Much forgotten is the fact, expressed by AP Government and AP U.S. History teacher Julie Caracci, that history involves just as much reading as english.

“I read a lot. I like to read modern stuff, history stuff. Fiction a lot — I really like fiction. So yeah, reading’s good for you,” Caracci said.

Those historical texts tell their own kind of story. One that requires its own kind of interpretation; historians would agree that some form of the Iliad’s Trojan War happened, but did the Greeks build a giant wooden horse? That seems unlikely. After all, the Iliad is just a Greek story. One that gives you a glimpse into their answer to the question “Why?”

“By teaching history, I feel like I’ve become a storyteller in some way,” Caracci said.

That story, like all of us, grows, matures and ultimately changes over time. We live vastly different lives than the Greeks; yet, like Athenian democracy, we take many of our ideas from them. What they are not, however, is infallible. The Greeks had many cruel and vicious ideas as well — just look at how Socrates treated women — but without the study of those ideas it would be impossible to understand how our society has grown into its present form.

“You can make a lot more meaning of the present, I think, if you know the past. Otherwise, it’s kind of like you’re not rooted in anything,” Caracci said.

If knowledge is power and power is freedom, then the path to freedom comes through knowledge. The humanities is its own unempirical kind of knowledge. In its own way it answers the question “Why?” and in doing so gives you the freedom to explore yourself without being tied down in empiricism or faith. Apropos of nothing, the humanities allow the freedom to explore what is unquantifiable — ideas.

Your donations directly fund the Lane Tech student journalism program—covering essential costs like website hosting and technology not supported by our school or district. Your generosity empowers our student reporters to investigate, write, and publish impactful stories that matter to our school community.

This website is more than a publishing platform—it's an archive, a research tool, and a source of truth. Every dollar helps us preserve and grow this resource so future students can learn from and build on the work being done today.

Thank you for supporting the next generation of journalists at Lane Tech College Prep!

Theo is a senior in his second year at The Champion. A part of the Omega program, Theo is passionate about reading, writing and history. In his free time,...