Coming to terms with femininity

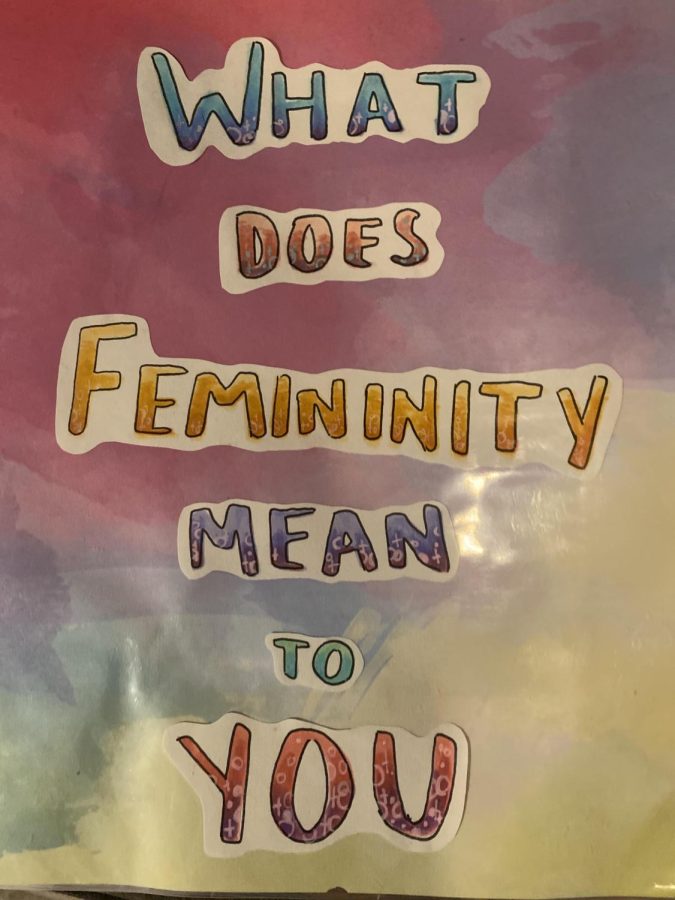

“What Does Femininity Mean to You?” First page of the Women In Lit Project, “Finding Femininity” by Megan Main-Duplechin, Lizzie Lenczowski, Dillon Klemm)

When I was younger, I hated the song “Call Me Maybe” by Carly Rae Jepsen. There wasn’t a basis for this hatred; maybe her voice annoyed me, or the lyrics felt cheesy. All valid criticisms, but looking back, I realize now what I hated about it. I didn’t allow myself to like it because it was a “girly girl” song. I didn’t want to be one of those girls that liked it — I didn’t want to be overly feminine.

Femininity is one of the most controversial and complex qualities of humanity. With its more negative connotations — often coming from misogynists — it can equate to weakness or otherwise as a quality of being lesser.

As a person born a woman who doesn’t quite feel like one, I’ve always seen femininity as somewhat of an arch nemesis. Simultaneously, it feels like one of the ties holding me down to the gender binary and also like an old friend I can’t quite part with.

The definition of femininity is quite literally the qualities of being a woman, but what are those qualities? No woman is the same, just as no human being is the same. How can I be so detached from something that doesn’t quite have a clear source or meaning?

At the Women in Lit Fest this year, one project I came across spoke to this idea perfectly. Three juniors at Lane, Lizzie Lenczowski, Megan Main-Duplechin, and a good friend of mine, Dillon Klemm created a scrapbook/presentation which gathered responses from various people of various backgrounds about their perceptions of femininity.

Seeing the different responses changed my perception of femininity in myself. I realized that maybe, femininity does not always equate to womanhood. I don’t need to reject it entirely to feel like myself; in fact, rejecting it always felt off, but I refused to accept it.

When I first realized I might not be cisgender, and even before then, I would subconsciously reject anything “traditionally” feminine: dresses, makeup, and “Call Me Maybe.” Eventually, I wouldn’t even let myself say things that might seem too feminine, or sit in feminine ways, or even let myself feel even remotely feminine.

This did not feel right in any regard. I’d gone too far. I wasn’t being true to myself — I was being true to the voice in the back of my mind that was an amalgamation of every misogynistic ideal that had been taught to me. The Women in Lit project was a meaningful development in realizing and accepting more of myself than I ever have before.

Lenczowski had a similar reevaluation of her ideas while working on the project.

“I never really struggled with it, but the more I think about it, I can’t really define it,” she explained. “I guess I kind of attribute femininity to some of those things, like to flowers and stuff. I guess, since it’s kind of hard to come up with a clear definition, I’m attributing it to things.”

Every person has their own definition of femininity — or lack of a clear definition. I would align with the latter. I can visualize femininity similar to Lenczowski: pink, flowers, dresses. It’s the traditional, stereotypical things that I can’t find myself in.

However, the primary realization I came to regarding my own femininity was that it is untraditional. It didn’t consist of the flowery stereotypes; it was internal. Not being the most stereotypically feminine person, or not being a woman, doesn’t mean I can’t align with certain aspects of femininity.

For example, many men, especially within pop culture and the LGBTQ community, have been aligning themselves with femininity more recently. “Men who are able to embrace their femininity, they seem a lot more free than a lot of the men that are so violently against femininity,” Lenczowski explained.

But why do I not experience that same freedom? I think because of the experience I’ve had as a person who was assigned the expectation of femininity, I can’t feel the same freedom of femininity as someone who is rebelling against norms by doing so.

However, many women feel empowered by their femininity and by taking control of it for themselves. It’s been hard, but I feel maybe I can do the same.

By taking back femininity and explaining that it’s possible to do without being a woman, because femininity and womanhood don’t equate, I can truly accept who I am in full. For some people they might be connected, but for me, they’re two separate ideas. It’s up to each person.

Many responses in the Women in Lit project related femininity to abstract ideas, or feelings; but for me, and I’m sure many others, it’s hard to visualize it that way. I applaud those who can fully explain and understand their own femininity; I’d like to think I’m slowly working towards that myself.

Trying to visualize or describe a concept is something that takes a lot of skill. It’s like how you can’t really describe a color perfectly; you need to see it to understand it.

That’s what I think makes it so hard for men to express their femininity. They’ve never allowed themselves to experience it or understand it in others, so they reject it fully and only see the parts of it that can be properly described: the pink, the pretty, the gentle.

Look at it for more, and try and experience it fully and authentically, and then the world will come to really understand it.

It’s a bit hypocritical for me to ask others to accept femininity when I can’t do it myself, but I’ll try and work on it too. The world will be a substantially more understanding place when everyone does their best to acknowledge themselves fully, including their femininity.

Take a look inside yourself, and I’ll do the same.

Your donations directly fund the Lane Tech student journalism program—covering essential costs like website hosting and technology not supported by our school or district. Your generosity empowers our student reporters to investigate, write, and publish impactful stories that matter to our school community.

This website is more than a publishing platform—it's an archive, a research tool, and a source of truth. Every dollar helps us preserve and grow this resource so future students can learn from and build on the work being done today.

Thank you for supporting the next generation of journalists at Lane Tech College Prep!

Mallory is a junior and this is her first year writing for The Champion. She’s in the Omega Program, and has a passion for writing. At school, she is...