By Matt Wettig

It is the 1960s, tensions are brewing between the United States and the Soviet Union. They are in the midst of the Cold War.

With the threat of a nuclear war looming, many concerned citizens are constructing fallout shelters. A Chicago Reader article, dated April 14, 1994, counted the number of these shelters in Chicago at 10,000, though it is not known how many have fallen into disrepair. Little do most students know, there is a nuclear fallout shelter beneath Lane.

The Lane Daily, Lane’s newspaper predating The Warrior reflects a lot of the anti-Soviet sentiment of the time period.

“At present, the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics and China are the biggest villains on the world stage,” reads a Lane Daily article titled “Why World War 3?” from May 8, 1963.

Lane’s basement is designated as a fallout shelter, but other than that, from what I have found, not much is known. The basement became a shelter in the early 1960s. 1974 alum and current teacher Mr. Keating remembers seeing “dozens upon dozens of military rations” in the basement while accompanying teachers on errands there.

Fallout shelters were also a topic of discussion of the Lane Daily. There is a mixed opinion on their usage, an excerpt from a November 19, 1962 issue reads, “We are a powerful, respected country, known as the preserver of freedom in the world. We have powerful defenses, prestige, and confidence in our way of life. But where is our confidence if we have bomb shelters to run to? It seems as this is a gesture of defeat, that we are admitting we cannot stop the enemy, and cannot stand up to him. We should rather die like men, not afraid to face death, knowing there is a better world, than to die like shivering dogs in a hole. Better still, why not why not exert our efforts to preserving peace so no one dies?”

The Lane Daily also conducted an interview with a teenager from Cuba, who was in the United States on a student visa. The boy, Harry Garcia, spoke of the general public initially being in favor of Fidel Castro, but “a year into his dictatorship, the educated people of Cuba realized that Castro’s Communist ties were too close for comfort.”

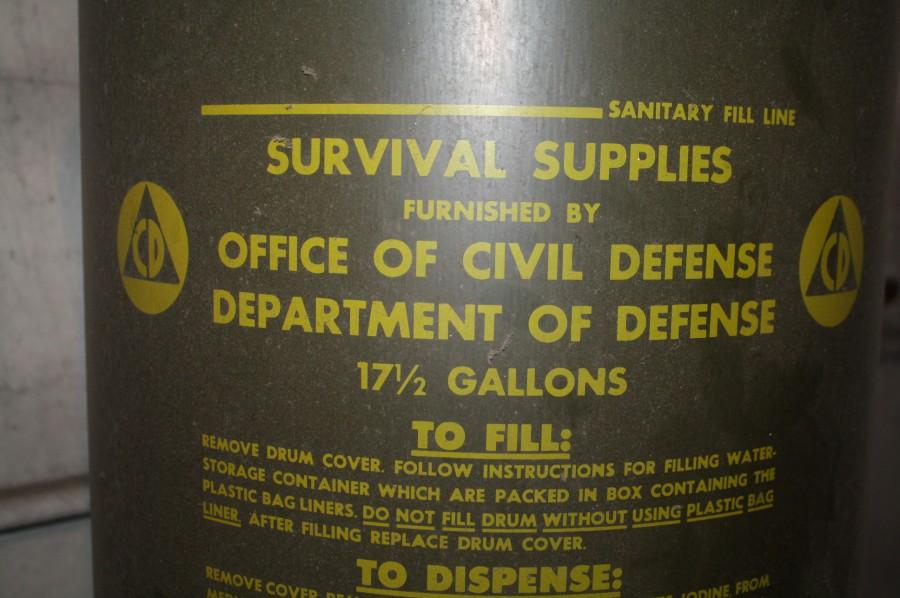

Today, the majority of the nuclear fallout shelter signs, that used to dot the halls of the basement, are now gone. Only a few remain. These, along with three US Department of Civil Defense water containers are the only remnants. The containers are the same military rations that Keating references. He believes the rest were moved out a number of years ago when the school underwent asbestos abatement.

Keating says that students performed nuclear disaster drills, much like the disaster drills that go on today. They evacuated into the halls, but from what Keating describes, never the basement.

The fact that the basement was a shelter was a widely known fact to students, Keating believed, to act as a source of comfort.

“I was never really worried,” Keating said. “I always thought ‘well we’re the US, we’ve got more nukes than anyone, but the underlying thought [of a nuclear attack] was always there.”