School of champions, school of rebels: Lane’s heritage of activism

Tracing dissent at Lane from the 1970s to today

Michelle Weiner most remembers the almost palpable feeling of a changing world, the notion that in every direction, at every hour, in every corner of Chicago, something was happening.

“If you can imagine, this is 1970,” said Weiner, the Lane Tech Alumni Association President and Class of ’76 Lane alumna, in an interview with The Warrior. “We’re in Vietnam. People are wearing headbands and tye-dye and all that stuff.

“It was exciting. There was so much going on. I mean, as a young woman back then, Ms. Magazine had just been published for the first time. The first female CEO of a Fortune 500 Company had just been named, that was the Washington Post. The ERA [Equal Rights Amendment] was going on, Nixon was going on, Watergate was going on.”

Robin Washington, Lane Class of ’75, agrees. “You were very much aware — you could not have lived in Chicago and not at least been aware that the world was changing and that Chicago was one of the major points of it.”

Though the cultural revolution of the 60s and 70s permeated every sphere of American society from fashion to business to literature, the nexus of this tumult was in politics and social involvement. More broadly, in the idea that the lay citizenry could force those in power to heed their voice, and that protest, discussion and the strength of populist movements could enact change.

After the 1968 Democratic National Convention and the assassinations of Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert Kennedy, for example, widespread protests “left 11 Chicagoans dead, 48 wounded by police gunfire, 90 policemen injured and 2,150 people arrested,” according to the Encyclopedia of Chicago.

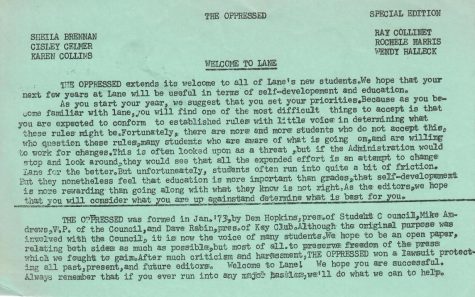

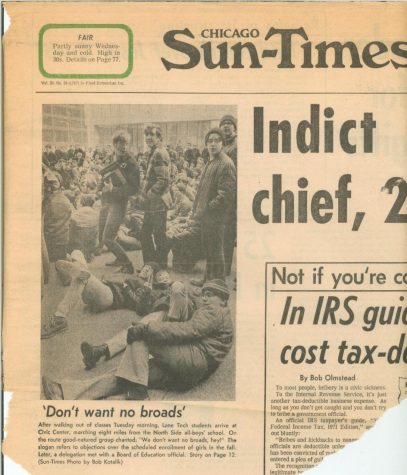

Lane was not immune to this spirit of dissent: the early 1970s saw protests against male-female integration, as well as the creation of The Oppressed, an underground student newspaper.

The paper, formed by then Student Council President Dem Hopkins, was a self-proclaimed bulwark of the freedom of the press, and aimed to challenge a school environment where students were “expected to conform to established rules with little voice in determining what these rules might be,” according to the paper’s January 1973 issue.

The writers critiqued what they perceived to be Lane’s complete discouragement of individuality. They repudiated attendance policies that sustained the belief that “the most effective ways to get kids into class is to threaten them with punishment,” according to the March 1974 issue. In their issue labeled VOL. II no. 2, they wrote a treatise describing their philosophy of education and condemning “when an imitation teacher gets on the scene and is allowed to waste time in the classroom.”

Hopkins and his peers faced disciplinary action for distributing the paper, and in response, sued the school for First Amendment violations. In 1973, the United States District Court for the Northern District of Illinois ruled that the students could continue distribution so long as it did not “materially and substantially interfere with the discipline of the school,” according to the lawsuit. They then began distributing the papers outside of the school on campus.

Weiner recalls the dichotomy between the lawn and the school’s interior.

“There was just a lot of electricity in the air, but once you were in the building, it was pretty quiet,” she said. “It was outside. People weren’t passing a whole lot of stuff out in the hallways — it was outside on campus.

“You would walk up onto campus and they would be out with their backpacks in front of the auditorium doors handing out their mimeographed copies of The Oppressed.”

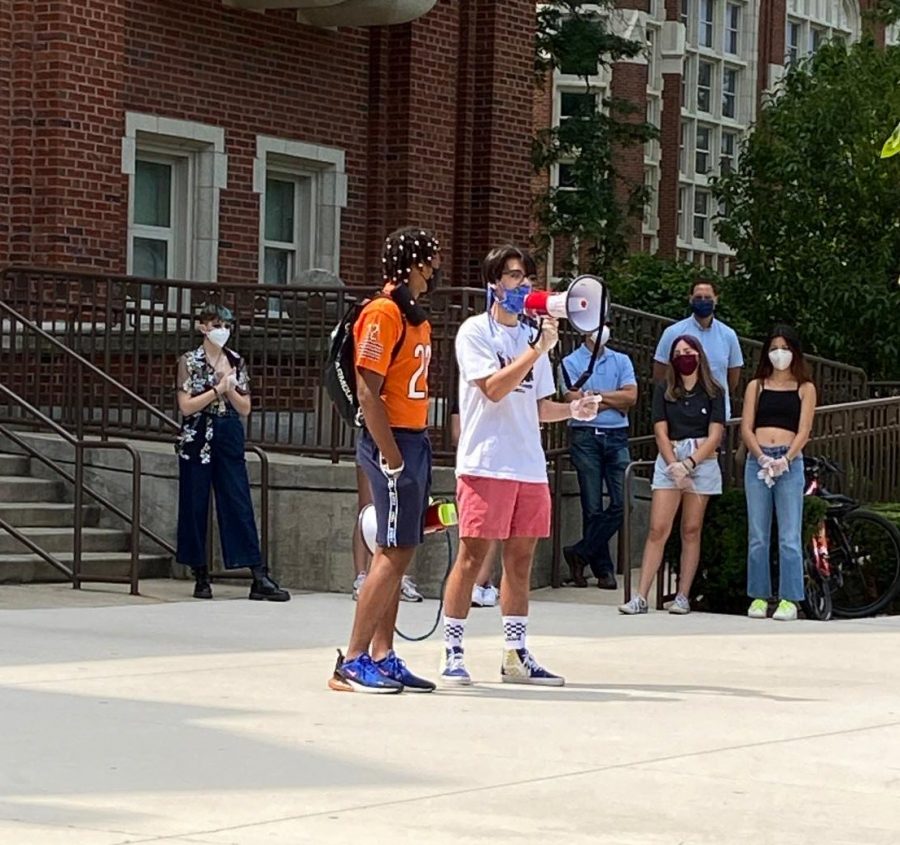

At a time when the coronavirus pandemic has forced school buildings across Chicago to close, the image of students protesting on the Lane lawn is strangely familiar. Twice in the past two months, Lane students have protested against racial inequality in education; once demanding changes to make curriculum more diverse, and a second time against school resource officers (SROs), which are police officers stationed in schools. There has also been an impressive online presence of students advocating to change Lane’s Indian mascot.

Indeed, even the societal circumstances between then and now are eerily similar. Just as racism, riots and civil unrest in the 60s and 70s influenced The Oppressed’s formation and other protest activity, so widespread revolt in the wake of George Floyd’s death at the hands of police has led to a new wave of youth activism, including at Lane.

“It’s a pattern for Lane Tech,” Weiner said. “The current controversy is removal of the mascot or symbol and what that means to tradition and what that means to identity, and the scariness of what’s ahead without knowing. In 1971, the same thing was happening with the prospect of young women entering the school, which was unheard of, and what would happen, and it would ruin the school, and it would never be the same.”

But though student dissenters are no longer protesting female integration and distributing their newspaper on the lawn, the spirit of disobedience remains.

Today, this spirit manifests in Lauren Marut, Lane Class of 2020, who has spearheaded the fight for racial justice at Lane.

Marut’s first foray into activism came when she organized a Juneteenth march with the Chicago Children’s Choir, with which she has sung since 3rd grade.

“We gathered about 70 alumni singers to perform Anti-Apartheid music, Civil Rights Era music. [We were] preserving the historical intention and integrity of the music; we don’t want to just sing songs to sing them, but to really understand the message behind them,” Marut said, adding that the group marched from the South Loop to the Daley Plaza.

Since then, Marut’s advocacy has been geared toward inequities within CPS; on July 11, she and Armani Washington, another 2020 Lane graduate, organized a protest for a more inclusive curriculum in solidarity with a Latin School of Chicago protest the same day. Marut also aided community organizer Ugo Okere in leading a protest against school resource officers (SROs) in Lane.

It was not easy work, Marut said, but she felt a duty to protest.

“I don’t know if there is a specific thing that compels me to be an organizer,” Marut said. “I just couldn’t stand to see the injustice that my Black peers face every single day.”

She continued, “Community mobilization is pretty hard, but I’ve been at the school for six years and know a lot of people, so as a 2020 graduate, I felt I was in a great position to organize.”

Robin Washington experienced firsthand the tumult of the 1960s Chicago protests when he worked as a newspaper delivery boy. He says that community mobilization is common to both protest movements.

“The most important thing is, I just think the energy of it all, getting people out there, totally resonates with what I experienced growing up,” he said. “That somehow, throughout all of this stuff, people got the message and they’re out there. It is inspiring to see all the different races. I think it speaks, finally, [to] a younger generation that is more reflective of what America is.”

For Marut, this period in history is a perfect storm for activism — “The murder of George Floyd definitely revitilized the Black Lives Matter movement around the country,” she said, and she has begun challenging the notion that older people are always right, “which empowered me to become an activist.”

Weiner, too, says that young people’s ideas are now uplifted instead of disregarded, which has encouraged them to continue advocating.

But at Lane, Weiner says, “there’s always been a level of activism — Lane has always had the best and brightest critical thinkers in my biased view.”

Looking back at Lane’s history of activism — the anti male-female integration protests, the Oppressed’s distribution, and now this current wave of anti-racism and police brutality protests — this indeed seems to be the case.

“That’s the interesting thing about Lane as a reflection of the times,” Weiner said, “and it absorbs some of that angst that happens in our culture, inside the school and outside the school.”

Your donations directly fund the Lane Tech student journalism program—covering essential costs like website hosting and technology not supported by our school or district. Your generosity empowers our student reporters to investigate, write, and publish impactful stories that matter to our school community.

This website is more than a publishing platform—it's an archive, a research tool, and a source of truth. Every dollar helps us preserve and grow this resource so future students can learn from and build on the work being done today.

Thank you for supporting the next generation of journalists at Lane Tech College Prep!

Naturally having harnessed the wisdom that comes with age, Finley, now a senior in her third year with The Champion (formerly The Warrior), spends her...