‘Lane of Things’ expands to Wrigley Field

Sensor nodes to be implemented at Wrigley Field through multi-month project

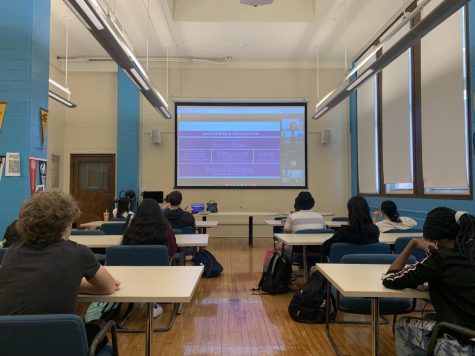

Satya Basu, far left, from Perkins+Will Architecture Firm and Robb Drinkwater, next to Basu, and Douglas Pancoast, far right, from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago speaking with Ms. Wozniak’s ICL class about narrowing down project questions that each team will be addressing with the Cubs organization.

April 5, 2018

Lane Computer Science students will soon deploy sensor nodes to collect data and analyze multiple environmental aspects of Wrigley Field.

Some examples of sensor nodes that the Cubs organization is interested in include temperature, audio levels and even emotional aspects of the ballpark, according to Vice President of Technology Andrew McIntyre.

McIntyre said that one of these collections could entail the interaction between a fan and a concession stand through a happy face/sad face system.

“That’s that raw, real time feedback that you’re capturing as soon as that interaction happened, not after the game, through a survey or anything else,” McIntyre said.

This is one of the many examples of a data collection that is currently in the works through a multi-month project that will be implemented at Wrigley Field. This is the first time Lane of Things has expanded its project to an outside organization.

Lane of Things is part of the larger initiative of Array of Things, which works “to collect real-time data on the city’s environment, infrastructure, and activity for research and public use,” according to their website. This is Lane of Things’ third year of operation.

Data is collected through sensor nodes, which are small devices that are able to gather and process sensor information from their environment, as well as communicate with other nodes, according to IGI Global.

The project is currently in phase four of five which consists of the introduction of various new assets, according to McIntyre. Phase five will eventually consist of finalizing the project and will be more fan-focused.

“I think a key mission of our organization is to really deliver a world class fan experience, and so when it comes to collecting data that we can learn more about how the fans are experiencing the ballpark and what can improve their experience, we’re always very excited to get on board with those types of programs,” McIntyre said.

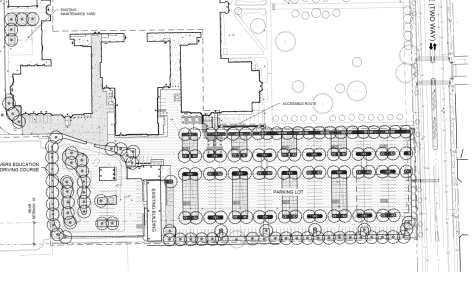

The project will not only be implemented in the ballpark but also in the surrounding areas of Wrigley Field, according to Mr. Solin, a Computer Science teacher.

He said some surrounding areas may include The Park at Wrigley, the new Wrigley offices and neighborhood businesses that would be willing to participate.

There are a total of 138 Computer Science students participating in the project, according to Mr. Law, Computer Science Department Chair. The students are divided into approximately 36 teams, each consisting of a total of four students from the Innovation and Creation Lab (ICL) as well as the Physical Computing Lab (PCL).

The groups are overseen by Solin, Law and Ms. Wozniak, a Computer Science teacher.

Law said that each team has one student from PCL who is the leader of the circuit and programming while the other three ICL students are in charge of designing other aspects of the sensory node.

Students can use the data they collected in order to analyze a particular area, such as how much vibration a staircase experiences during game day, according to Law.

“That data would be stored in a cloud somewhere and once the data collection period is over, they will pull all that data and create some sort of analysis,” Law said. “So that’s the exciting part of Lane of Things is it’s whatever the students decide to do.

The initial idea for the project was developed over the summer, according to Solin. Lane of Things then contacted the director of community affairs at Wrigley Field and began discussing a project plan.

“When we heard about the Lane of Things and some of the sensor data that you guys [Lane Computer Science students] are capturing, we started to think about our own evolution,” McIntyre said. “We thought it could be a really good mix.”

Lane of Things is funded through a grant by Motorola Solutions, so the project will also be funded by Motorola Solutions and not Wrigley Field, according to Solin.

“For two years we had deployed and outfitted Lane with these sensor nodes, and we thought about what options we might have to deploy somewhere else to analyze and evaluate a different environment, not just the environment of Lane,” Solin said.

Solin and Law said that they wanted a project where their students would be able to use their knowledge and skills in order to apply them to solve real problems.

“This is as real world as it gets,” Law said. “Each little team is now essentially a consulting company and they all have to satisfy their client’s needs in some way or form.

In comparison to previous years of Lane of Things projects, Law said that students were only able to work with people within their class period. This year, however all students are working with people from different class periods in order to take advantage of what each student specializes in.

Each group has a detailed project management spreadsheet that includes tabs of when the group met and what they discussed in order to track their progress, according to Law and Solin.

In addition to spreadsheets, students have access to three professors from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago whom they can contact via email regarding any questions they may have, according to Law.

“With projects like this, we want to stay on top of them to make sure it gets done because the Cubs are going to want this information and at the same time, we don’t want to micromanage them,” Law said. “We don’t want it to become Mr. Law’s project or Mr. Solin’s project; we want it to remain that particular team’s project.”

The teams are currently brainstorming questions that they are interested in collecting data for, before actually building their nodes, according to Megan Altman, Div. 853.

“A lot of questions were about where fans go throughout the game, so one of our questions was which doors are people more likely to exit through or what time do they usually leave which, parking lots do they like to use, what bus stops do they want to go to and a lot of stuff with the surrounding neighborhood as well,” Altman said.

Altman is in both PCL and ICL and will be in charge of the hardware and software for her team’s nodes in addition to retrieving data from the sensors.

“I think designing something for a client, making something that’s not just for your own personal use but for somebody else — it’s definitely a very different experience because it’s no longer your own creative control,” Altman said. “You’re kind of working with somebody else who has their own goals.”

Despite there being a total of 36 teams, not all teams will deploy a sensory node; some will work collaboratively, according to Solin.

“Some groups might be building a device or a node that displays information or gives feedback based off of another group’s nodes,” Solin said. “There may be multiple groups collecting a deployment of the same type of node in multiple spaces.”

Solin said that there are multiple factors to take into consideration for the project and that students will have to take several trips to the ballpark.

“We have to consider power, so these things [sensory nodes] can run on batteries but only for short periods of time so we need to have power supplies,” Solin said. “We need to make sure we have WiFi connectivity and if not, we need to have LTE cellular connectivity for the devices.”

There is currently no set date yet for the project to be implemented at the ballpark, according to Solin. But, the groups’ projects must be finalized before senior graduation.

“We can’t deploy until after opening day, which is the beginning of April, but we still need to get out there and survey the space to see where things might go,” Solin said. “We have a lot of things to consider; this is hard but it’s fun because it’s hard.”

Both Solin and Law hope that their students understand the importance of this opportunity, in terms of using their knowledge to real-world applications.

“The ultimate goal is for students to develop an awareness of not just what they’re current environment is like by what kind of data their body is giving off, but also how their data is being collected,” Law said. “We want them to be able to manipulate that environment, we want them be a part of that process.”