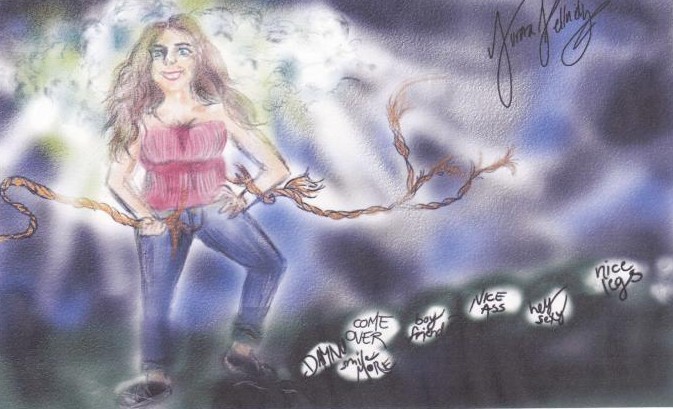

Catcalling: Who gave you the right?

OPINION

My friend and I stepped out of the CTA train car. The clock read 11:30 p.m. I had just had the most amazing day at Lollapalooza. The dancing, music and laughter was still ringing in my ears and pulsing in my sore feet.

I knew we weren’t in the best neighborhood, I knew we weren’t here at the best time of night, and I knew we were wearing what some might call provocative outfits, yet none of these things were on my mind.

And why should they be?

As we walked onto the sidewalk, I saw a group of men standing together at the corner we had to cross. Instantly, I could feel the anxiety and fear spreading through my body. We walked by quickly, and as we passed the men turned our way.

“Hey sexy, nice ass. How bout you come over here and get to know us?” one of them said. The other men sneering at us, mumbling in agreement. My face burned. I could feel the shame of my outfit, the invisible burn of their stares at us as we walked away, but most of all, the anger that was boiling up inside me.

Who gave these men the right to speak to me? Who gave them the right to make sexual comments about my body? Why did my friend and I have to feel afraid walking down a street at night?

Catcalling is verbal harassment. It is not a compliment. It is not welcomed. A boy or man who sees a girl or woman walking down the street has absolutely no right to make comments about her body. No matter who the woman is, being talked to in a disrespectful way automatically makes the man seem like he has the power.

Catcalling is also just downright creepy. What goes through an adult man’s brain when they make sexual comments about a teenager’s body, especially someone who is young enough to be their daughter?

According to Stop Street Harassment’s website, in a 2008 survey, almost 81 percent of female respondents were the target of sexually explicit comments at least once from an unknown man. 81 percent. That is a huge and disturbing number.

It isn’t the same men that are catcalling all of these women. Catcalling has become a normality, something passed down generation to generation. When a man catcalls a woman in front of a young boy or adolescent, it shows a child that it is OK to say an uncomfortable, sexual comment to a woman without her permission, thus continuing the cycle.

Although some people may think a single comment is harmless, I think it means everything. The man is not hurting the woman, not physically assaulting her, but he is asserting dominance, leading to low self-esteem and confidence, which is just as serious.

Grace Winter, Div. 850, a victim of multiple accounts of catcalling and harassment, said that she does not take catcalling as a compliment.

“It makes me view myself as an object than more of a person,” Winter said.

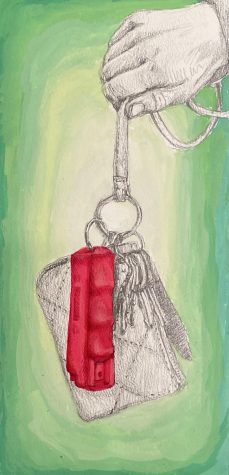

For Winter, catcalling has escalated into dangerous situations. One day, she was on her way home when a man started calling out to her, talking about her hair color and saying he knew her mom. Winter told the man that this was untrue. The man then started cursing at her and yelling for her to get in his car. Thankfully, Winter made it to safety in a nearby coffee shop, but the situation changed her.

“I’m scared to look at men on the street because I think they’re going to do something, going to say something, so I just keep my head down when I walk past them,” Winter said.

Speaking up to harassment is the first step to change, but you have to know when it is safe. For Winter, in that situation, standing up could have put her in danger. Feeling the situation out is crucial. Depending on the time of day, neighborhood, and amount of catcallers, saying something may be the right decision, or it could put you in danger. Being city kids and knowing the risks, it’s important to find a balance.

If you feel it is the right time and place to say something, let it out. Changing the cycle is the only way to break it.

Dr. Jacqueline Gilson, Lane’s psychologist, says we are all programmed in different ways: either as a person who demands dignity and respect from people, or as a person who reacts more passively to conflict. By speaking up to a catcaller, you’re telling them verbal harassment is not tolerated any more.

“We don’t remember the things that are routine, we remember the things that are really off or odd,” Gilson said. “If a teen approaches their catcaller, you have to believe that because it’s so unusual, it might trigger a different reaction in them going forward because it’s outside the lines.”

The words you choose to say to a catcaller could affect their reaction and the amount of change it instills in them.

“If you come off very combative you’re not going to get your point across,” Gilson said. “I think something that really tends to quiet people is ‘How would you feel if someone said that to your sister, or your mother?’”

These simple, yet powerful words connect the act of catcalling to the way men see women.

Every time I’ve spoken up to a man catcalling me, there is a pause. A moment before the anger and confusion where something moves in their brain. That pause is what could change the way catcallers act, as well as the way they view and treat women. That pause is the power.

As I look back at that night after Lollapalooza, I’ve thought a lot about my actions. I remember clearly the anger boiling up inside me. I swung around and stared at the group of men.

“Shut the f**k up!” I screamed.

The men stopped talking for a second, staring at me in surprise. After a moment, I could once again hear their angry shouts saying how ugly I was and that I should come back and apologize, but I could feel the change in the air. That small pause made these men see me in a different way. I was no longer a victim, another girl accepting their uncomfortable words.

I turned on my heels and walked swiftly away. I didn’t regret what I had said at all.

Thank you!! We met our goal for the 2023-24 school year! Your contributions covered our annual website hosting costs, which are no longer covered by our district/school. Student journalists at Lane Tech use this archive to research past coverage of various topics and link to past stories to offer readers additional context for current stories. Thank you for supporting the award-winning reporting and writing of journalism students at Lane Tech College Prep!

Background information on why the school district no longer allows our school to cover web hosting costs:

https://lanetechchampion.org/12583/uncategorized/special-coverage-impact-of-soppa-on-cps-students-teachers/

https://lanetechchampion.org/11702/opinion/staff-editorial-cpss-soppa-policy-is-choking-students-learning-and-the-champion/

Simone Brenner is an A&E Editor for the Warrior. She is passionate about writing and learning new things about the people at Lane and events going...